Il miracolo economico italiano

Alla metà del 1950 l’Italia era ancora intrappolata negli anni grigi del dopoguerra.

L’industria, limitata alle regioni del Nord-ovest, produceva perlopiù beni di prima necessità, alimentari e tessili; quasi la metà della forza lavoro era assorbita dalle campagne, solo nell’8% delle abitazioni si potevano trovare, insieme, acqua corrente, luce e servizi igienici.

Poi, in modo così improvviso da giustificare il termine ‘miracolo’, tutto cambia.

Cambia innanzitutto il mondo industriale, che riesce a intercettare e soddisfare la domanda estera in campo chimico, meccanico e metallurgico. Cambia di conseguenza il lavoro, con un riversamento della manodopera dalle campagne alle fabbriche, dal Sud al Nord.

Cambia il potere d’acquisto dei lavoratori, il cui reddito pro capite, dal 1954 al 1964, aumenta del 63%.

Cambiano le aspirazioni degli italiani, che sopravvissuti a un cinquantennio in cui si erano registrati quasi 10 anni di conflitti che ne avevano logorato la resilienza, ora possono liberarsi dall’idea di quotidianità fatta di sussistenza per abbracciare nuove prospettive.

LA CASA E LA DONNA

Lavatrice, l’alleato delle donne degli anni Cinquanta.

Con il suo cestello girevole e l’oblò ipnotico, quest’elettrodomestico diventa l’oggetto del desiderio in qualunque fiera campionaria.

Ma non è il solo, perché in quei capannoni rumorosi e affollati campeggia anche quel monolite che il patron della Ignis Giovanni Borghi definisce “l’amico di famiglia”: il frigorifero. Alla base dello sviluppo della sua azienda c’è l’immagine di sua madre, che da bambino vedeva impegnata ad accendere il fuoco o a bruciare con una pompetta a petrolio il cibo andato a male.

Ora non è più necessario spaccare il ghiaccio nei lavatoi d’inverno, o fare la spesa tutti i giorni: frigorifero e lavatrice diventano alleati delle donne, che lentamente ritrovano il tempo da dedicare non solo alla cura dei figli, ma anche di loro stesse, ad attività professionali e a quegli hobby che, grazie al benessere economico, permettono di dar voce alle proprie inclinazioni e passioni.

Amici di famiglia, alleati preziosi che alleggeriscono le incombenze... e il portafogli: acquistare una lavatrice significa sacrificare 3 mesi e mezzo di uno stipendio medio, per il frigorifero si arriva addirittura ad investire sei mesi di lavoro.

Ma una nuova abitudine, la rateizzazione, permette di acquistare gli elettrodomestici anche alle classi meno abbienti.

Strumenti di libertà

Gli anni del boom economico non hanno significato soltanto uno sviluppo industriale senza precedenti, ma anche un cambiamento nel modo di concepire la vita e i ruoli sociali: le differenze tra classi si facevano via via più sfumate e la donna non è più soltanto una madre e una moglie, ma anche una lavoratrice e una persona con passioni e tempo libero.

Nel 1963 infatti, la legge n.7 del 6 gennaio vieta il licenziamento delle lavoratrici per causa di matrimonio, mentre la n.66 del 9 febbraio dello stesso anno afferma il diritto delle donne ad accedere a tutte le cariche, professioni ed impieghi pubblici. Una svolta epocale: i nuclei familiari si arricchiscono e i ritmi mutano radicalmente.

Ad alleggerire le incombenze domestiche ci pensano gli elettrodomestici, che fanno capolino in sempre più case italiane. Non sono più beni di lusso, ma strumenti di libertà, acquistabili a rate anche grazie agli strumenti che compagnie come Reale Mutua offrivano ai propri Soci.

"Alleggerite le vostre responsabilità!" - con un volantino pieghevole, nel 1964 Reale Mutua presenta ai propri Soci le opzioni di rateizzazione disponibili per l'acquisto di beni di consumo come auto, frigo e tv.

Il tempo ritrovato: l’energia elettrica e le donne

Hans Rosling, medico e statistico svedese, in un Ted Talk del 2010 racconta cosa abbia significato la diffusione degli elettrodomestici nelle case dal punto di vista delle donne e dei bambini.

"Avevo quattro anni quando vidi mia madre caricare una lavatrice per la prima volta. I miei genitori avevano risparmiato anni per poterla acquistare e il giorno in cui fu messa in moto, anche mia nonna volle essere presente. Lei era ancora più emozionata: per tutta la vita aveva acceso il fuoco per scaldare l’acqua, e lavato il bucato a mano per sette bambini. Chiese di poter premere lei il pulsante, prese una sedia e si godette l’intero ciclo di lavaggio. Era incantata. ‘È una magia’ diceva.

Perché la lavatrice fosse una magia me lo fece capire subito mia madre: ‘Ora che abbiamo caricato il cestello’ mi disse ‘tu e io andiamo in biblioteca’.

...I CONSUMI

Il 27 novembre 1957 viene inaugurato a Milano il primo supermercato in Italia, in viale Regina Giovanna. Così lo presenta un servizio dell’epoca: “Ed ecco dagli Stati Uniti giungerci i supermercati. Il cinema hollywoodiano ce li aveva fatti conoscere e quindi gli italiani non hanno avuto la benché minima difficoltà a impadronirsi del semplicissimo sistema. Si entra, si guarda e si prende ciò che serve. Ogni prodotto accuratamente confezionato ha il suo prezzo e eventualmente il suo peso bene in vista. Ultimati gli acquisti si raggiunge la cassa e si paga. A tale proposito è da notare che i supermercati sono fatti in modo che è impossibile uscirne senza passare davanti alla suddetta cassa. Non si tratta mica di diffidenza, Dio ce ne guardi: è un semplice accorgimento appositamente studiato per la comodità dei clienti”.

I simboli del benessere

Negli anni Cinquanta i salari aumentano e l’inflazione è stabile: molte famiglie possono finalmente acquistare beni fino ad allora impossibili da possedere, primi fra tutti gli elettrodomestici, disponibili a rate. I beni diventano status symbol, testimoni del nuovo benessere che la penisola attraversa insieme ai propri abitanti.

Scooter, Vespe e Lambrette, ma anche Seicento e Cinquecento popolano le strade, da Nord a Sud, con i loro colori più disparati, come un caleidoscopio in movimento che mostra al mondo la personalità di ogni guidatore. Con l'intensificarsi del traffico, nel 1971 le RC Auto diventano obbligatorie: di fronte a questa nuova esigenza, Reale Mutua si adopera per offrire ai propri Soci soluzioni che sappiano unire convenienza e massimo grado di tutela.

Il mercato immobiliare si diversifica, offrendo nuove soluzioni abitative, e la Compagnia investe su Milano e Torino, centri nevralgici dell'epoca.

Beni di consumo che si legano a doppio filo con il mondo assicurativo, immerso in una società e in un mercato in rapida ascesa.

LA MOBILITÀ E LE STRADE

In Italia nel primo dopoguerra, per la prima volta nella storia si avvia l’esperimento di separazione del traffico in base alla velocità di scorrimento: Il 21 settembre 1924 viene inaugurato il tratto Milano-Varese dell’Autostrada dei Laghi. Dalla Seconda guerra mondiale la rete di comunicazione italiana esce devastata: le ferrovie distrutte, 14.700 km di strade devastate, 140 ponti crollati. Il 19 maggio 1956 si inaugurano i lavori dell’Autostrada del Sole, dal 1957 al 1963 la produzione degli autoveicoli aumenta di 5 volte. Gli italiani però continuano a spostarsi principalmente sulle due ruote. Nel ’58 per un operaio possedere un’automobile rimaneva ancora un sogno irrealizzabile, ma di lì a poco, una martellante campagna pubblicitaria che abbatteva il tabù dell’orrore per i debiti a favore dell’acquisto rateizzato, unita alla nascita della Fiat 500, contribuì a cambiare le cose.

La silenziosa rivoluzione delle strade d'Italia

Era il 1936 quando Ferdinando di Savoia assicurava la sua FIAT 521 con una polizza auto Reale Mutua contro il furto e l’incendio. All’epoca, le auto erano ancora miraggi sulle strade italiane, ma vent'anni dopo, il rumore dei motori scandisce i tempi in città. Bastano pochi semplici numeri: a metà degli anni Cinquanta in Italia c’era un’automobile ogni 77 abitanti; a soli due anni di distanza, una ogni 39 abitanti. Valerio Castronuovo la definisce “silenziosa rivoluzione”, quella che ha investito le strade d’Italia.

Una rivoluzione non solo silente, ma anche veloce, che in poco tempo porta gli italiani a stipulare più polizze nel ramo Auto che non nel ramo Vita e che richiede alle compagnie di assicurazione di adeguare la propria struttura per affrontare questi nuovi bisogni.

Utilitarie, auto di lusso, strade urbane e Autostrade, di cui Reale Mutua coglie tutto il potenziale, investendo nella loro realizzazione attraverso società quali ATIVA e SITAF; ma anche nuovi documenti e nuovi obblighi portati dall’aumento del traffico, tra RC Auto e Convenzioni per l’Indennizzo Diretto.

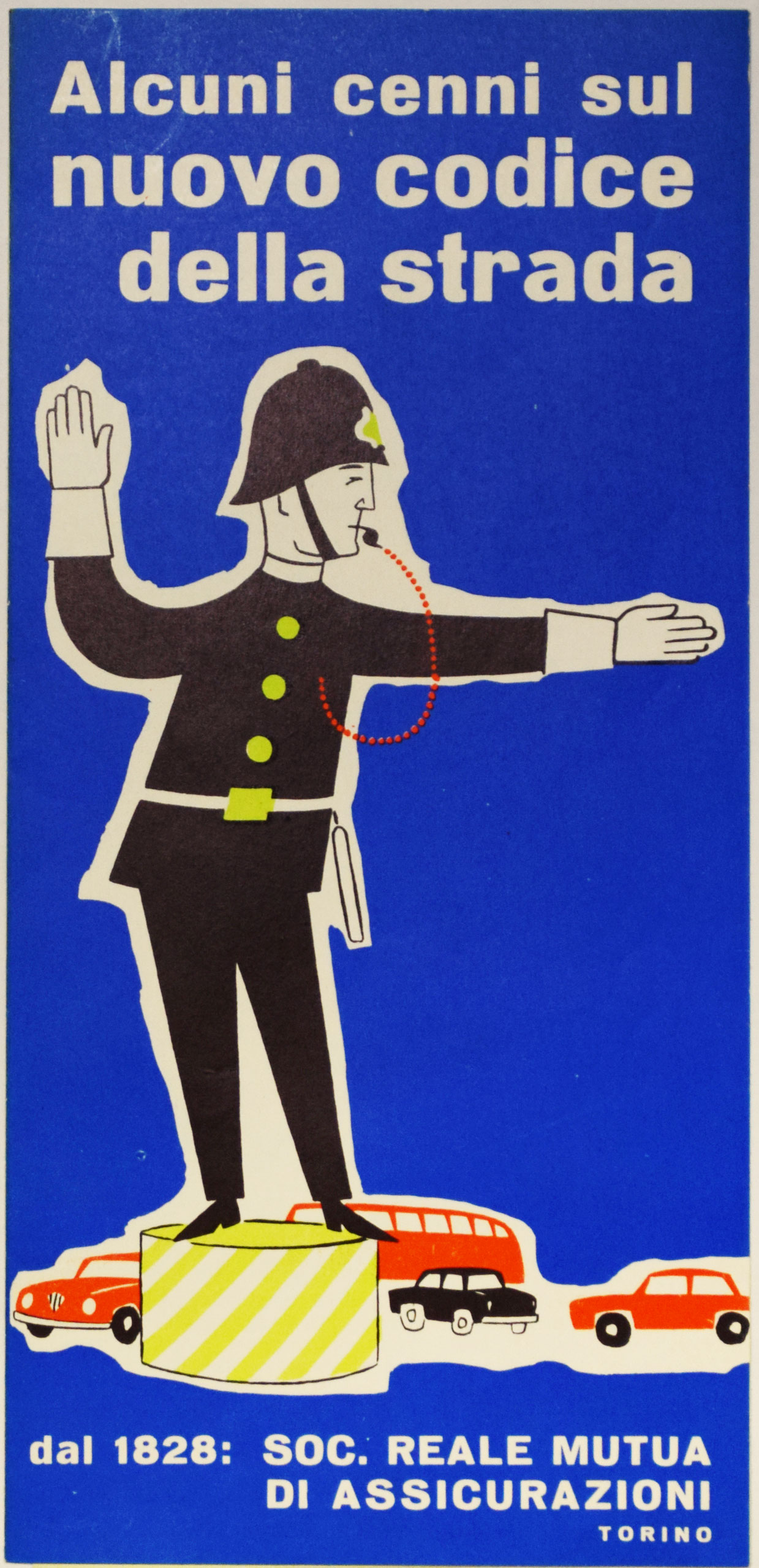

Durante l'estate del 1959 - entrò in vigore il Testo Unico sulla circolazione stradale, approvato con il d.P.R. 15 giugno 1959 n. 393, composto da 147 articoli, più i 607 dell'annesso regolamento.

Il testo risolve la disastrosa situazione della segnaletica stradale post bellica, ancora non normata e distrutta dal conflitto appena concluso. Vengono stabilite nuove regole riguardanti forma, dimensione e colore.

500 l'automobile minima

500 di cilindrata, 500 chili, 500 mila lire: nel 1957 esce la Nuova 500 che, dopo una tiepidissima iniziale accoglienza del primo modello, diventa una vera e propria icona del design italiano – prima vettura a vincere il prestigioso Compasso d’Oro – e contribuisce significativamente a cambiare la mobilità degli italiani.

Così è presentata al suo debutto:

“Eccola qua, le concediamo il posto d’onore, il privilegio dell’apertura, lo spazio che nei quotidiani è riservato all’articolo di fondo. Carlos Salamano, pilota e pioniere, ce la presenta con legittimo orgoglio. Motore posteriore di 479 centimetri cubici, 2 cilindri in linea e raffreddamento ad aria. Ampio e comodo abitacolo per due passeggeri, spazio retrostante i sedili capace di ospitare almeno quattro valigie, oppure per chi li preferisce alle quattro valigie, due bambini.

Dunque buon viaggio alla fantastica velocità di 85 chilometri all’ora, realizzabili con appena quattro litri di benzina, vale a dire una ventina di chilometri al litro (gli americani hanno degli accendisigari che consumano molto di più).

...LA TELEVISIONE

Il 3 gennaio 1954 la Rai apre, con la telecronaca dell’inaugurazione degli studi di Milano e dei trasmettitori di Torino e di Roma, il regolare servizio delle trasmissioni televisive.

Al momento gli abbonati sono 90, che diventano 24.000 dopo un mese, 88.000 dopo un anno, 1 milione dopo quattro.

Concepita come strumento di informazione e educazione, la televisione dedica solo una piccola parte all’intrattenimento: il momento più importante è lo spettacolo teatrale del venerdì sera.

Nel 1955 Sanremo passa dalla Radio alla TV; nel 1957 arriva la pubblicità, con Carosello: 10 minuti segmentati in narrazioni da 1 minuto e 45 secondi, chiuse da 30 secondi dove viene presentato il prodotto. Nel 1959 si alza il sipario sullo Zecchino d’Oro e nel 1960 si accendono le luci degli studi di Non è mai troppo tardi, che insegna a leggere e a scrivere a una nazione che conta ancora 4 milioni di analfabeti.

Poi i programmi storici come Lascia o raddoppia e quelli sportivi, soprattutto il calcio e il ciclismo: La domenica sportiva, in onda dal 1953, è in assoluto il programma più longevo della televisione italiana.

Il 4 novembre 1961 Mina saluta così la nascita del Secondo Canale, Rai2 “Ed ora ditemi che sono retorica, che sono una sentimentale ma io a questo secondogenito televisivo voglio dedicare un brindisi”. La televisione italiana nasce negli anni del boom economico, lo alimenta e da esso è alimentata, ed è lo strumento di unificazione linguistica, sociologica e culturale di un paese che ancora non ha imparato a sentirsi nazione.

Reale Mutua e il piccolo schermo

Reale Mutua è rimasta a lungo affezionata ad una comunicazione cartacea, approdando in TV per la prima volta solo nel 1985 con uno spot che strizza l’occhio alle atmosfere del Gattopardo.

"C’è una grande assicurazione che vi tratta da re, anzi da Soci: Reale Mutua Assicurazioni, Soci non semplici assicurati" è il suo claim. Il primo di una lunga serie di messaggi che, in pieno spirito mutualistico, mettono al centro la protezione, la prevenzione e il rapporto diretto con i propri Assicurati, che per Reale Mutua sono Soci.

Il tempo è passato e le narrazioni sono mutate, ma in ogni forma di pubblicità la Compagnia ha sempre affidato la sua immagine a firme prestigiose: da Dolci a Saffirio, passando per Armando Testa, i messaggi di Reale Mutua non vogliono solo raccontare la storia del Gruppo, ma far sentire lo spettatore parte di essa.

Che emozioni o possieda un’innata verve comica, la comunicazione televisiva di Reale Mutua mette l'individuo al centro, ogni volta con scenari e sapori differenti.

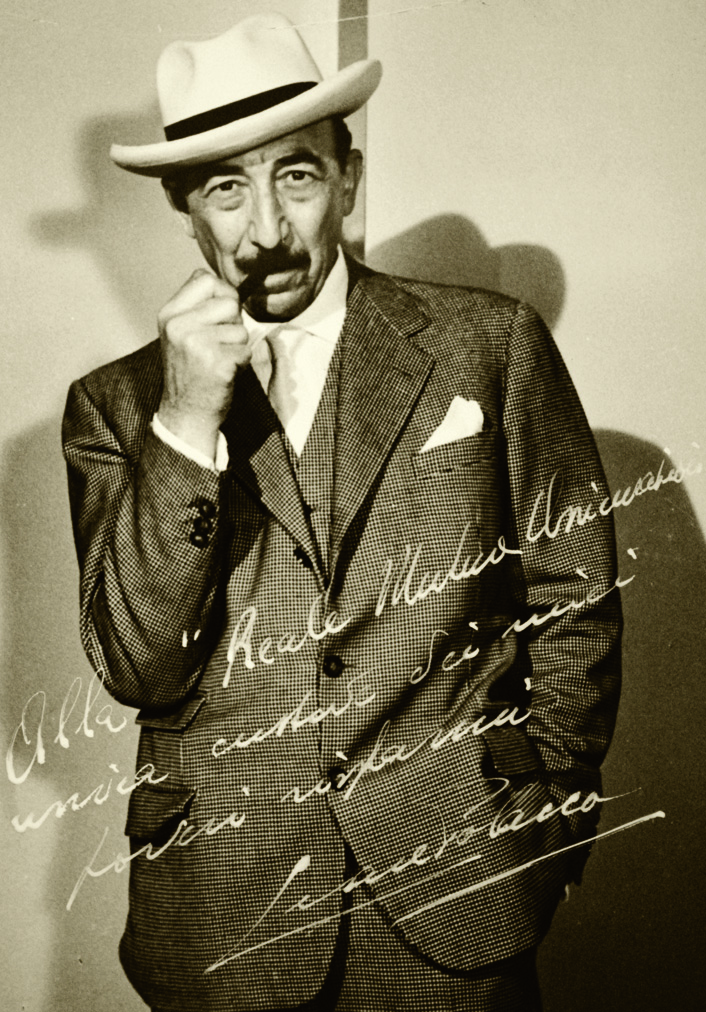

Foto autografata con dedica di Cesare Polacco: "Alla Reale Mutua Assicurazione, unica custode dei miei pochi risparmi".

Il fenomeno e la brillantina: Cesare Polacco

Cesare Polacco, alias il quasi infallibile ispettore Rock, ha risolto i suoi mini-gialli su Carosello dal 1957 al 1968 in episodi sceneggiati da Luigi Magni, Furio Scarpelli e Lina Wertmuller da 1 minuto e 45 secondi, a cui era aggiunto un ‘codino’ pubblicitario di 30 secondi dove venivano presentati i prodotti della linea Linetti.

...IL TEMPO LIBERO

Negli anni ’50, quando per la classe operaia e impiegatizia la resa lavorativa si misura non più con il prodotto finito ma con il numero di ore lavorate, nasce il concetto di tempo libero. Simbolo di evasione e svago sono le gite domenicali in automobile, le vacanze estive, gli eventi sportivi: calcio e ciclismo, da seguiti negli stadi, sulle strade e alla televisione.

Sport e arte per un divertimento "reale"

L’acronimo C.R.A.L. (Circolo Ricreativo Aziendale Lavoratori) comparve per la prima volta nel dopoguerra, ma già dal 1927 Reale Mutua offriva ai propri dipendenti attività ricreative attraverso il Dopolavoro: dalle bocce al canottaggio, passando per il calcio, il ciclismo, la marcia, il tiro alla fune e la scherma, l’entusiasmo dei partecipanti era palpabile.

Di particolare successo fu la creazione di una compagnia filodrammatica intitolata a Fulberto Alarni, pseudonimo del dipendente Alberto Arnulfi, poeta e commediografo dialettale piemontese molto apprezzato da Edmondo De Amicis, autore del celebre libro Cuore.

E poi conferenze di ogni genere, corsi di formazione e iniziative come “Natale Reale”, che ancora oggi coinvolge intere famiglie con spettacoli e doni.

Un ventaglio di possibilità per gli impiegati di Reale Mutua, che potevano dar voce alle loro passioni più recondite.

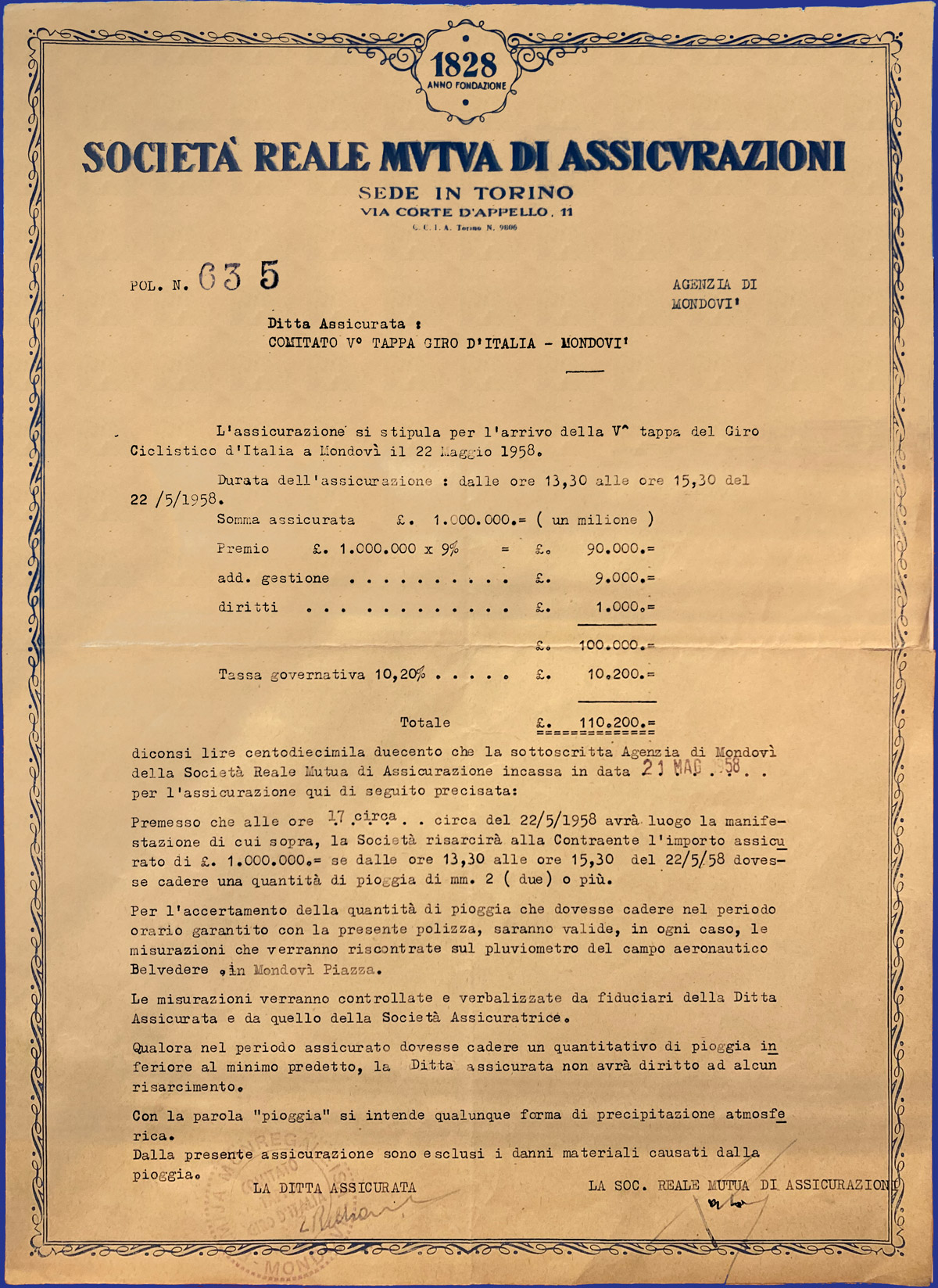

Per tutelarsi dal maltempo, il Comitato della V Tappa del Giro d'Italia del 1958 assicura l'evento presso la Compagnia. Nel documento si legge: "la Società risarcirà alla Contraente l'importo assicurativo di un milione di lire se dalle 13.30 alle 15.30 del 22 maggio 1958 dovesse cadere una quantità di pioggia di mm. 2 o più".

La tappa della tempesta

«Ma dove vai bellezza in bicicletta, così di fretta pedalando con ardor?» cantava Silvana Pampanini in “Bellezze in bicicletta”, dove Silvana, il suo personaggio, pedala insieme a Delia verso il loro sogno più grande: entrare nella compagnia di Totò.

Sono gli anni Cinquanta. In sella alle proprie fedeli compagne, tutti canticchiano questo motivetto, come se ad ogni pedalata e ad ogni fischiettio si potesse pedalare più forte. Come se tutti si sentissero come Silvana e Delia, alla ricerca di un sogno da realizzare.

È lo stesso ritornello che riecheggia il 22 maggio 1958, alla quinta tappa della quarantunesima edizione del Giro d’Italia, l’ul

...